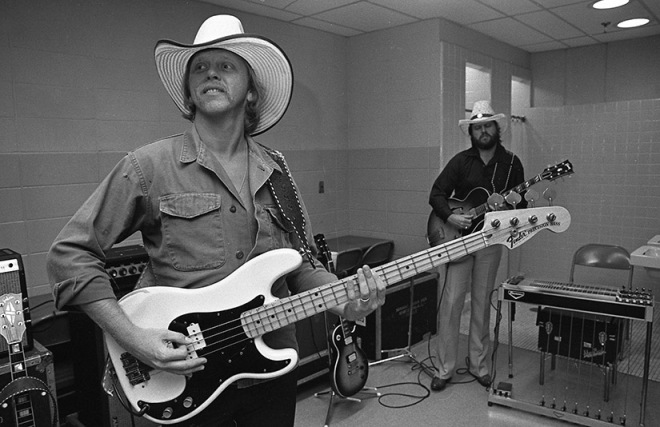

Tommy Caldwell and his brother Toy Caldwell of the Marshall Tucker Band tune up backstage in Philadelphia before a concert in 1979 at The Spectrum. (Photo by Tom Priddy)

Tommy Caldwell and his brother Toy Caldwell of the Marshall Tucker Band tune up backstage in Philadelphia before a concert in 1979 at The Spectrum. (Photo by Tom Priddy)

This story was first published in print on July 22, 1979.

By TOM PRIDDY

Reprinted from The Greenville News-Piedmont, July 22, 1979

WESTBURY, N.Y. – Tommy Caldwell needed a new hat, and he needed it fast.

A tall steel hauler named Frank had Caldwell’s last one, and by now was probably stopping at every truck stop south of Philadelphia to spout off about it:

“Guess where I got this hat. C’mon, just guess now. You’re not gonna believe it.”

Tommy Caldwell almost didn’t believe it either.

The steel hauler had come within an arm’s length of getting a busted head instead of a new hat just the night before. Frank made a brief appearance on stage as Caldwell stood on the elevated platform at the Spectrum in Philadelphia, playing bass guitar with the Marshall Tucker Band.

Frank jumped from the balcony, landed right behind the sound board and headed for the row of cowboy hats on stage, arm outstretched for the white Stetson worn by Tommy’s brother, Toy, who plays lead guitar.

He didn’t make it. About a half dozen security men and roadies grabbed every part of him that could be grabbed and tried to see how many different directions they could carry him at once.

Tommy and Toy grimaced a little, shook their heads and never missed a lick. Frank was headed out of their lives at about 30 miles an hour. Or so they thought.

Two hours later the Spectrum was cleared out and Tommy was headed for the back portal where the limousine waited. There was Frank. Reincarnated. Still in one piece.

Still looking for a hat.

This time he shifted tactics.

“I’ll give you a hundred-dollar bill for that hat,” said Frank.

Tommy rolled his head back in disbelief. The trucker pulled out the crumpled cash.

Tommy took the bill. Frank took the hat.

Tommy was philosophical. “My daddy didn’t raise no fool,” he said.

How about a replacement?

But that left something of a problem. What would Caldwell do without a hat? After Philadelphia the six-man Marshall Tucker Band boarded their bus and he pondered the problem as they headed for Westbury, L.I., where they’d stay for two shows at the Nassau Coliseum. The boys from Spartanburg, S.C., had sold the place out both nights — nearly 30,000 tickets.

Tommy could play his bass without a hat — lots of people do it every day — but he sure didn’t want to. “I think he feels kind of naked without one,” said Paul Riddle, the band’s drummer.

So as soon as Tommy got off the bus he headed for the Yellow Pages. So did the band’s manager, Joe McConnell. But this area of Long Island was a mecca to concrete and superhighways, and the prospects of finding a good Western store were slim.

“I called about three places,” McConnell explained, “and they said, ‘You know, there ain’t many cowboys around here.’”

•

Aaaahhhh, but that’s where they were wrong.

There are plenty of closet cowboys on Long Island — and in the rest of the Northeast — and the Marshall Tucker Band has every one of them slap dang in the palms of their hands.

If that wasn’t evident before, this tour would prove it.

Cut back briefly to Philadelphia the afternoon before, where up in Room 303 of the Stadium Hilton Inn a curly-haired man with his feet on the bed is doing a bit of high-energy promotion.

On the other end of the phone is Kal Rudman, owner of the Friday Morning Quarterback, one of the nation’s big radio tipsheets. Suffice it to say that a favorable mention by Rudman is worth a lot of airplay and a lot of record sales.

On this end is Barry Gross, product manager for Warner Bros., a record executive who is spending a few days traveling with the band. In the band’s entourage of 29 people he is the only who looks like a record executive. He’s the only one wearing a jacket — and it’s black velvet at that.

Promoting the band

His job is to help make the band look good, sound good and feel good, and he’s giving Rudman a super pitch. Gross wants him to come to the show that night at the Spectrum, a large arena used mostly for basketball and hocKey.

“Trust me,” Gross says, “you’ll be impressed. It’s the tour this summer that everyone’s talking about. There’ll be more action than the Sixers and the Flyers combined.”

The pitch is basically the same everywhere: you have to see the show to believe it. And this year — finally — the Marshall Tucker Band has the support of some of the best pitchmen in the business to spread the word to the uninformed.

That’s why 1979 is a big year for the boys from Spartanburg. After six years and six gold records on the tiny Capricorn label, the band is now touring behind their first album for Warner Bros. — an industry giant. And Warners is making a “very major major commitment” to support the band, says Gross.

“I feel like there’s no way that this band couldn’t get to the top, and there’s no way that they won’t,” says McConnell.

Working on the Capricorn label somehow has gotten them pegged as another Southern boogie band, a tag that may be limiting their chances for hit records. They have never had a No. 1 record, for example, although “Heard It in a Love Song” made it to No. 11 in 1977. Thanks partially to the boost from that single, the “Carolina Dreams” album sold a million copies. Their new album, “Running Like the Wind,” has been as high as’No. 30.

Instead of hyping the band’s image, Gross simply has to get people to understand it.

“They’re not a Southern boogie band,’’ he says. “They’re an American band.”

A surprising one, at that. “A lot of people wouldn’t think that this is an act that could come into New York and sell out two nights two months in advance,” says Gross. But this month that’s just what happened. And it’s the same throughout the Northeast, where the band is drawing large crowds despite the gas shortage.

On this particular tour they would sell out at Nassau (where Tommy would perform in a brand new hat — “I had to go all the way to Manhattan to the Stetson dealer”) Springfield, Mass., and New Haven. They would come within 500 or 600 of selling out in Boston, Philadelphia, Syracuse and Rochester.

Caldwell has seen these crowds a thousand times before. Cowboy hats dot the audience. A spray-painted sign hangs from the balcony (this one in Long Island), “Ward Melville loves the Marshall Tucker Band.” A Georgia flag appears in one of the front rows. “The people get crazy,” he says, trying to understand the reaction in towns where they don’t even sell grits.

“I think they like the music because it’s kind of honest,” adds Toy. “It doesn’t have any jive to it.”

There’s a lot of cowboy spirit alive all over the country, says Tommy, and “they can come see us and let it out for one night.”

Carol and Harriet, two Philadelphians in their 20s, don’t need the Marshall Tucker sales pitch. They’re already hooked right down (or is it up?) to their cowboy hats. They’ve been waiting most of the day on an understuffed couch down in the lobby of the Hilton to catch a glimpse of one of their favorite bands.

They grabbed Paul Riddle, in T-shirt and shorts, on his way to the elevator, and Harriet had him sign copies of three of her Marshall Tucker albums. “I wasn’t able to bring mine,” said 25-year-old Carol. “I’ve got them taped up on my wall.”

Harriet smiled at what she thought was an understatement. “You can’t even see the white of the wall through ‘em all,” she said.

“They’re nice people, basically,” says Carol, explaining the band’s appeal to two suburban Philadelphians. She’s wearing a white warmup jacket with the Marshall Tucker logo hand embroidered on the back. (“I did it myself.”)

“And good music,” says Harriet.

“Southern hospitality,” says Carol.

“Yeah, Southern hospitality,” smiles Harriet.

Critics hooked, too

But this isn’t one of those bands beloved by the crowds and sneered at by critics. Concerts by the Marshall Tucker Band have been getting great reviews for years. “The Mind-Blowing Marshall Tucker Band” is the way a Philadelphia alternative weekly headlined a story previewing the band’s concert. The New York Post gave the Long Island shows their highest recommendation.

Even the staid New York Times has said the band’s “Fire on the Mountain” is “deliriously lyrical.”

The band has a comfortable sound, and members attribute that largely to the fact that the band’s close-knit atmosphere gives them the right peace of mind. Something like: the family that plays together, stays together.

When recording, for example, the band now rents a house in Coconut Grove, Fla., near the recording studio, and takes “a lot of the road crew that really doesn’t have to be there,” says business manager McConnell. “It’s good to have them all together to sit down at 1 o’clock for a big meal. It sounds corny,” he adds, “but it’s like a family.”

The family ties began as early as the late 1950s, when rhythm guitarist George McCorkle played with lead guitarist Toy Caldwell. Nothing real organized, you understand. But it was a start.

Things got more formal in the following decade. Many of the band members — plus McConnell — went to school together. “We’ve all known each other since about the 10th grade of high school,” says Toy, “about 11 or 12 years. And I’ve known George all my life.”

Their big high school group was the Toy Factory, which included Toy and Tommy, George McCorkle, Doug Gray and a couple of other guys. Toy and Tommy did a stretch in the Marines after that (“A family tradition,” says McConnell), McCorkle went into the Navy and Gray the Army.

They all wound up together again at a club called The Ruins in Spartanburg after the service, and one night after a McCorkle-Riddle band played on stage the deal was closed to start the Marshall Tucker Band. It was named, in what has now become a legendary story, after a friend by that name, who was an elderly, blind piano tuner.

“We’re six totally different people,” Riddle said, “but we have one tie, and that’s Spartanburg. We grew up here, and that’s what’s great about Spartanburg. I don’t know another band that’s all from the same town,

“A lot of people here don’t really know what success the band’s had,” Riddle added, “which is fine. They don’t think of us as any different.”

Offstage, in fact, they aren’t.

Toy Caldwell, lead guitarist, raises Arabian horses on his farm. He’s just gotten two national champions. He also enjoys deer hunting.

Tommy Caldwell, bass player, is a close-to-scratch golfer who plays whenever he has a chance. He also likes to fish and turkey hunt.

George McCorkle, rhythm guitarist, and singer Doug Gray are drag racing fans.

Gray and Jerry Eubanks, who plays wind instruments, spend a lot of time with their motorcycles and trail bikes.

And Paul Riddle, the drummer, is a “raquetball nut” who also jogs on days he isn’t playing.

Home is a place for recuperating now, not performing. Their schedule puts them on the road for 10 days and then home for two weeks. That’s a schedule they’ve worked for, after playing endless tours in their early years. “My first kid, I didn’t really see her growing up,” says Toy, the father of two girls. “I missed about her first two or three years.” He’s not missing out on his second one.

But as much as they enjoy being home, they’re uncomfortable playing anywhere nearby.

“When we play close to home everybody gets a little uptight,” says Riddle.

“We’re too nervous,” says McCorkle. “All our folks are out there” in the audience.

Riddle credits their home ties with keeping them from getting swelled heads. “A lot of my buddies (in other bands) are living too much in the fast lane. They never really get off the stage.”

•

The first time the Marshall Tucker Band cruised into New York City to play a concert they were riding in a brown Dodge van. They were used to sleeping on the floors and struggling to find leg room. It was not traveling at its finest.

They played to crowds of about 20 people a night at Kenny’s Castaways,

On this Saturday afternoon as they hit the Garden State Parkway and cruised over the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge their only apparent problem was that Bjorn Borg and Roscoe Tanner — at center court at Wimbledon — were dissolving into a series of diagonal lines on the miniature Sony. Since about 1974 the band has had a customized Trailways Golden Eagle. You can’t miss it — it’s the one with the band’s logo painted on the side in shades of blue and yellow.

To picture the inside, imagine the classiest camper you’ve ever seen. Now imagine two of them. Now cover it with rough-hewn beams, leather upholstery and carpeting. Put in swivel chairs, bunks to sleep nine, a lounge area, drink box, stereo system with Bose speakers, a Sony TV and a Betamax unit and a sketch of horses in a wooden frame on the wall. Now you’re getting the picture.

Now imagine that’s not good enough and that you’ve already ordered its replacement.

Should be ready by fall

“We expect delivery on it maybe in August or September,” says business manager McConnell, the man who put his initials on the sales contract. To get exactly what they wanted, their driver. Buddy Carpenter, drove several Golden Eagles that Trailways had put on the block.

After picking one, the band agreed to a six-figure customizing job that will put two lounges inside, along with room to sleep 11.

While most bands prefer flying, the Marshall Tucker Band goes practically everywhere by bus. They were one of the first contemporary groups to try it. “It’s been a lifesaver,” says McConnell.

“The bus keeps you from burning yourself out, trying to keep up with airplane schedules,” says Toy, who can often be found sacked out in a bunk as the bus takes off. Plus, adds McConnell, “people are more apt to talk out their problems when they have to face each other day to day.”

Able to rub elbows together

Groups that fly can practically get by without seeing each other except on stage. McConnell prefers “rubbing elbows.”

And that the band does. By force and by choice.

There don’t seem to be any big ego conflicts in the band, and part of that may be because there are no stars. In fact, each night McConnell or road manager Jim Bannan has to issue passes to band members to make sure they can get around backstage without getting thrown out.

And each night when the show’s over, after the guitars are packed away and all the catered food is eaten, most of the band and the road crew slip down to the hotel bar.

There they have a chance to relax, have a couple for the road and talk about anything except music.

They blend right into the crowd.

They USUALLY blend right in, that is.

On this Friday night in Philadelphia in the Hilton bar a few fans were offering congratulations on another outstanding show — and who should show up again but Frank, the tall steel hauler, new hat in hand.

This time he corralled two or three band members, seeking more autographs.

“You don’t know how much this hat means to me,” he said as they squinted in the dim light, trying to find a place for their John Henrys.

“I wouldn’t take a million dollars for this hat,” he said. “I mean it.”

“I’m happy.”

-30-

This was my unforgettable Marshall Tucker experience at the New Haven Coliseum on July 14, 1979:

A friend and I, who’d earlier in the day gone to the SunFest at Yale Bowl to see The Beach Boys, walked into the Coliseum in the late afternoon through the backstage/loading dock entrance and hid separately until ticket-holders started coming in.

We had at least two hours to kill.

At one point, I took a stroll. A Hell’s Angels “security” goon saw me, got pissed off, and escorted me out.

I was walking in front of that scary guy. At one point, just before we reached the exit, he hauled off and slugged me in the back of the head. It was vile and really hurt.

I went straight to the Sheraton Park Plaza Hotel where the bands stayed and asked at the front desk for Marshall Tucker’s manager.

I was given a room number and told I could go up to see him.

I told him my story. He was so empathetic and angry. He told me “I’ll take care of you. Let’s go back there. I want you to show me the guy who attacked you.”

We went back shortly before Orleans (“Dance with Me” and “Still the One”) came on stage to open.

I found the gang member and pointed at him. He saw me do it.

The manager then found the head thug of the Hell’s Angels and demanded that the goon be kicked out of the venue. That was done.

Then the manager, whose name may’ve been Jimmie Johnson, gave me a great floor-seat ticket and a backstage pass.

One of the worst things that ever happened to me turned out to the most moving experiences I’ve ever had in achieving justice.

I’ve tried for years to find that manager and thank him, to no avail.

LikeLike